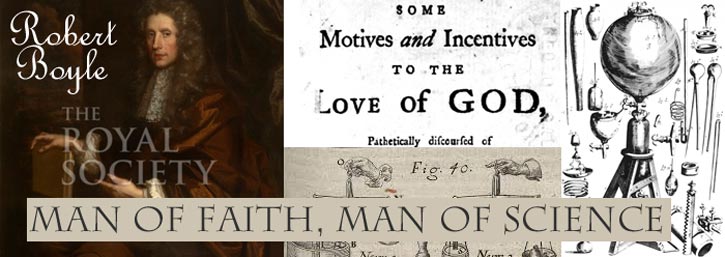

Man of Science, Man of God: Robert Boyle

Who: Robert Boyle

What: Father of Modern Chemistry

When: January 25, 1627 - December 30, 1691

Where: Born in Lismore Castle, County Waterford, Ireland

Irish natural philosopher Robert Boyle was a major contributor in the fields of physics and chemistry. One of the first to transform the study of science into an experimental discipline, he also championed the concept that all discoveries should be published, not withheld for personal profit and power--a common practice at the time. A devoted student of the Bible, he also produced multiple books and essays on religion.

The fourteenth child of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, young Robert learned to speak Latin, Greek, and French and entered Eton College before he was nine. He later journeyed abroad with a French tutor, including a visit to Florence, Italy, in 1641 to study with the elderly Galileo Galilei. In 1645, Boyle was put in charge of several family estates, marking the beginning of his scientific research. He earned a prominent place in the "Invisible College," a group of scientific minds that were instrumental in forming the Royal Society in 1663.

After moving to Oxford, Boyle and his research assistant Robert Hooke expounded on the design and construction of Otto von Guericke's air pump to create the "machina Boyliana." In 1660, he published his New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects Made, for the most part, in a New Pneumatical Engine. His response to critics of this work included the first mention of the law that the volume of a gas varies inversely to the pressure of the gas, what many physicists call today "Boyle's Law."

Though he also made discoveries regarding how air is used in sound transmission and the expansive force of freezing water, Boyle's favorite scientific study by far was chemistry, which he believed should no longer be a subordinate study of alchemy or medicine. In 1661, he criticized traditional alchemists and laid the foundation for the atomic theory of matter in The Sceptical Chymist, the cornerstone work for modern chemistry.

In addition to his scientific research, Boyle diligently studied the Bible. Along with the Greek he acquired in childhood, he learned Hebrew, Cyriac, and Chaldee so that he could read the text firsthand. His faith drove his experimental studies, as evidenced in his published works, and he believed that science and Scripture exist in harmony. Conflicts between science and the Bible, Boyle explained, were either due to a mistake in science or an incorrect interpretation of Scripture.

Even when some revelations are thought not only to transcend reason, but to clash with it, it is to be considered whether such doctrines are really repugnant to any absolute catholic rule of reason, or only to something which depends upon the measure of acquired information we enjoy.

His 1681 work A Discourse of Things Above Reason stressed the limitations of reason, which Boyle maintained should not be allowed to judge what God's revelation could or could not do. He believed the attributes of God can be seen by studying nature scientifically and that His wisdom is observed in creation.

When with bold telescopes I survey the old and newly discovered stars and planets when with excellent microscopes I discern the unimitable subtility of nature's curious workmanship; and when, in a word, by the help of anatomical knives, and the light of chymical furnaces, I study the book of nature I find myself oftentimes reduced to exclaim with the Psalmist, How manifold are Thy works, O Lord! in wisdom hast Thou made them all!